Para celebrar ambos, que cumplo 54 años (¡5+4=9!) el ¡27! de julio (2+7=9) y el 30 aniversario del día cuando el gobierno le concedió el permiso de Residencia a John Lennon, he puesto el “El Capítulo 27” de Nowhere Man: Los Ultimos Días de John Lennon. Esta es una forma de decirle gracias a quienes compraron Nowhere Man y quienes escribieron sobre el libro, convirtiéndolo en el éxito que es en Latinoamérica y España. Y quiero agradecer especialmente a todas las personas de México y Chile, que me dieron la bienvenida a sus países dispensándome su fina hospitalidad. Gracias, muchas gracias, de todo corazón.

***

El Capítulo 27

El 24 de agosto de 1981 fue un día sofocante—un día parecido a los de Honolulú—; cerca de doscientos miembros de la prensa y un puñado de espectadores esperan a que el famoso asesino sea conducido ante la Corte Suprema del estado de Nueva York, en el centro de Manhattan, y condenado por el delito de asesinato en segundo grado. La sala de la corte está abarrotada, y el nivel de energía es anticipadamente alto, con ese habitual tipo de anticipación previo a un concierto de rock. Todos estiran sus cuellos para ver con claridad a la estrella esposada, cuando entra en la sala con un chaleco antibalas debajo de una camisa azul oscuro. Chapman luce triste y patético, una presa entre las garras de algo que apenas entiende. Aunque no haya ya ninguna necesidad de juicio, hay la necesidad primaria de la humillación pública, un linchamiento verbal ante los medios de todo el mundo. Todos saben por qué Mark David Chapman lo hizo. Lo han sabido por ocho meses. Él lo hizo por la fama.

Y hay ciertamente mucha fama en los arrebatos de la sala de la corte esa día. Sería injusto sugerir que todos allí—todos los periodistas, testigos oculares, abogados—tienen el mismo objetivo: ser famoso. El juez Dennis Edwards, por ejemplo, parece bastante benigno, un viejo amable, de conducta moderada. En verdad, parece casi aburrido con lo que sucede, y tan soñoliento bajo la pesada humedad de agosto, que dormita por unos instantes en el banco, pero nadie parece advertirlo, u ocuparse de ello. Y el abogado defensor, Johnathan Marks, se conduce con aire de dignidad. Parece estar interesado en que su cliente tenga una audiencia imparcial.

Pero parece haber sólo una diferencia entre Chapman y virtualmente todas las demás personas que participan en esta audiencia: el acusado tiene ideas mucho más radicales acerca de cuán lejos está dispuesto a llegar para alcanzar la celebridad. Por un instante grotesco, Chapman, un cobarde perdedor, una cáscara vacía como ser humano, procura dominarse, es una actuación con el coraje de sus monstruosas convicciones. Él ha hecho exactamente lo que quería hacer, se ha transformado a sí mismo en el antihéroe mundial más famoso.

Por consiguiente, el aire está caldeado por celos vengativos. La gente está furiosa con Chapman no sólo porque él mató a John Lennon, sino también porque cometió un ataque brutal contra el statu quo, un acto de lucha de clases. John Lennon era un profesional muy exitoso, un miembro de la élite de poder. Y los profesionales más exitosos de la sala de la corte toman eso personalmente. Chapman se ha robado la fama de John Lennon, y ellos no están dispuestos a que la disfrute. Pero el triste hecho es que, de todas formas, la breve fama que ellos puedan alcanzar por esos días dependerá directamente de su relación con el asesino. Yo lo psicoanalicé a él. Yo lo acusé a él. Yo escribí una historia sobre él.

Los testigos oculares se han preparado bien para su momento ante los reflectores, para esa combinación de lo personal con lo histórico. Los psiquiatras podrían ser tomados por actores que audicionan para una miniserie de TV. Si puede hallarse un defecto en su actuación, es porque son transparentes en su mayoría. Sonríen demasiado. Parecen demasiado felices, demasiado presumidos, como si no les competiera cualquier noción anticuada de justicia, sino su lugar, pensar en contratos para escribir libros.

Los psiquiatras de la fiscalía repiten lo que han estado diciendo desde diciembre: Chapman estaba cuerdo, él sabía perfectamente lo que estaba haciendo, y lo hizo por la fama. Los psiquiatras de la defensa, desde luego, hablan de su esquizofrenia, de “la gente pequeña”, de su dolor.

Aparentemente, nadie se familiariza con la intrigante declaración de Yoko Ono sobre la reencarnación: “Tu hermano es la persona que tú asesinaste en tu vida pasada”. Por tanto, nadie se ha molestado en preguntar a Chapman: ¿Usted espera ser el hermano de John Lennon en su siguiente vida?

Los fans de Lennon añaden un toque surrealista a los procesos. Muchos de ellos llevan el pelo largo, como John lo usaba en el 68. Llevan lentes con bordes de cable y playeras con la imagen de Lennon. Ellos son más que los reporteros al menos en una relación de dos a uno, y están ansiosos por compartir sus opiniones con “los hombres de la prensa”.

“Mark David Chapman—opina un fan—era sólo un cabrón cobarde que lo hizo la fama.”

“Ahora él merece morir—añade otro—. Y yo estaría feliz de bajar el enchufe.”

Allen Sullivan, el fiscal, describe a Chapman como un hombre que “nunca mostró algún verdadero remordimiento” y está “interesado sólo en sí mismo, en su propio bienestar, en lo que le afecta, lo que le importa en este preciso momento”. Entonces insiste en que Chapman “lo hizo por la fama, por la exaltación personal, para llamar la atención sobre él, para halagar a su propio ego. El acusado estaba dedicado todo el tiempo a hacerse famoso”. Su prueba: Chapman quería que el fotógrafo Paul Goresh, quien previamente había fotografiado a Lennon cuando firmó la copia del Double Fantasy para Chapman, esperara hasta que Lennon regresara de su sesión de grabación, para que pudiera hacer la foto del asesinato.

Sullivan lo hace parecer como si el deseo por la fama fuera una cosa vergonzosa, un crimen en sí mismo. Pero sus palabras suenan huecas. Es un feo espectáculo que pasa por alto intencionalmente, el único hecho horrible que flota como una niebla sobre la sala de la corte. Es un hecho que nadie se atreve a mencionar: en Estados Unidos, en 1981, particularmente en una ciudad como Nueva York, la fama es una ventaja crucial, y el anonimato es una condición tóxica que puede conducir a la rabia asesina.

Holden Caulfield o John Lennon, en cuanto a eso, se habrían vomitado.

Antes de que el juez Dennis Edwards pronuncie la sentencia, a Chapman se le concede la oportunidad de hablar. Pero es poco lo que puede hacer para ayudarse a sí mismo. Chapman ya se ha declarado culpable. La evidencia en su contra es abrumadora. Es literalmente un arma humeante. El veredicto también podría estar predestinado. Él se ha enterrado en algún lugar por el resto de su vida. Alguna vez, la única duda verdadera era si él iba a estar en una prisión o en una institución para criminals dementes. Ahora no hay duda.

Visto como un mártir con un chaleco antibalas, se pone de pie y enfrenta al juez. Tiene su “Biblia” con él—su copia muchas veces hojeadas de El guardian entre el centeno—. “Yo he escogido este pasaje como mis últimas palabras”, jura—un juramento que pronto romperá—. Abre el capítulo 22, en el que Holden, tras ser expulsado de la escula por reprobar cuatro materias, dice a su pequeña hermana, Phoebe, lo que quiere hacer con su vida.

El asesino empieza a leer. “De todos modos, yo sigo imaginando a todos esos niños pequeños jugando algo en ese gran campo de centeno y eso es todo.” Está nervioso y al principio vacila. Entonces algo le da fluidez y pone empeño, su voz de repente es fuerte y clara, regular e impecable. Él ha ensayado bien, y hace justicia a Salinger.

“Miles de niños pequeños y nadie alrededor—nadie grande, quiero decir, excepto yo—. Y estoy parado al borde de un temible precipicio. Lo que tengo que hacer es capturar a todo el que empiece a acercarse al precipicio. Me refiero a que si ellos corren y no miran a donde van, yo tengo que salir de algún lugar y capturarlos. Eso es lo que yo hago todo el día. Yo sólo soy el guardián entre el centeno, y eso es todo.”

Éste es su mensaje y confesión. Mark David Chapman es el guardián entre el centeno de su generación; él ha asesinado a John Lennon para salvar a los niños.

Entonces Chapman dice a la callada sala de la corte: “Me siento como un peleador sangriento premiado en el round 27”. Ésas son las palabras exactas que había dicho a un psiquiatra en Hawai, tras su intento de suicidio. Pero nadie sabe de qué está hablando. Tampoco entienden el significado del 27, el triple de 9, ni el significado del capítulo 27, el capítulo perdido de El guardián entre el centeno, el capítulo de Chapman escrito con la sangre de Lennon. Son sólo unas palabras insensatas de un loco, que no significan nada.

El juez entonces pronuncia la sentencia y Chapman es sacado; con las esposas sale sin miedo de la sala de la corte, llevando la cabeza en alto, realmente brillando de orgullo. Él ha hecho lo que vino a hacer.

Instantes después, afuera de la sala de la corte, los medios, con sus bolígrafos, reflectores y cámaras listas, descienden sobre los testigos oculares de la fiscalía y Sullivan, el fiscal. Ellos son el equipo ganador. Están de pie en un nudo apretado y pequeño, arreglados para los reflectores, cada uno sonriendo ampliamente, empujándose el uno al otro hacia atrás, felicitándose interiormente por el trabajo bien hecho. Lo único que se echa de menos es el champagne, que probablemente vendrá más tarde, en una fiesta privada.

“¿Se hizo justicia?”, los medios quieren saber.

Por supuesto que se hizo justicia. El asesino muy probablemente pasará el resto de su vida en la cárcel.

Entonces no les queda nada más que hacer sino irse a casa y verse en las noticias nocturnas, mirarse fotografiados en los periódicos matutinos.

Con excepción de Mark David Chapman. Él continuará la gran caída descrita en la oscura profecía del capítulo 24 de El guardian entre el centeno. El Sr. Antolini, un viejo maestro de Holden—otro “pervertido” en realidad—, le dice: “Yo pienso que esta caída que estás conduciendo es una clase especial de caída, horrible. Al hombre que cae no se le permite sentir u oírse a sí mismo cuando toca fondo. Él sólo sigue cayendo y cayendo”.

Chapman pronto descubrirá lo que hay en el fondo del abismo “sin fondo”: un confinamiento solitario en Attica, poseído por los demonios.

Imagina que no hay posesión.

“Esto me mata.” Eso es lo que Holden Caulfield hubiera dicho, de todos modos.

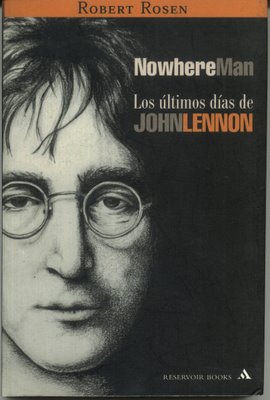

Desde Nowhere Man: Los Últimos Días de John Lennon © 2003, Robert Rosen.

© 2003, de la traducción, Rene Portas

© 2003, Groupo Editorial Random House Mondadori, S.L.

Barcelona, España

© 2003, Editorial Grijalbo, S.A. de C.V.

México, D.F.

***

The Translation

To celebrate both my 54th birthday (5+4=9!) on July 27 (!) and the 30th anniversary of the government granting John Lennon his green card, I’ve posted “El Capítulo 27” from Nowhere Man: Los Últimos Días de John Lennon. This is my way of saying thank you to all the Spanish-speaking people who’ve bought Nowhere Man, who’ve written about the book, and who’ve made it such a success in Latin America and Spain. And I especially want to thank all the people in Mexico and Chile who welcomed me to their countries with such graciousness and hospitality. Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!

***

Chapter 27

On the stifling day of August 24, 1981–a Honolulu-like day–about two hundred members of the press and a handful of spectators wait for the famous assassin to be brought before the New York State Supreme Court in downtown Manhattan and sentenced for his crime of second-degree murder. The courtroom is packed, and the energy level is high with anticipation, the kind of anticipation that normally might precede a rock concert. Everybody cranes their necks to get a good look at the manacled star as he is marched into the room wearing a bulletproof vest under a dark blue shirt. He looks sad and pathetic, a pawn in the clutches of something he barely understands. Though there is no longer any need for a trial, there is a primal need for a public shaming, a verbal tarring and feathering before the world media. Everybody knows why Mark David Chapman did it. They’ve known it for eight months. He did it for fame.

And there’s certainly a lot of fame up for grabs in the courtroom this day. It would be unfair to suggest that everyone there–all the journalists, expert witnesses, lawyers–has the same objective: to be famous. The judge, Dennis Edwards, for example, appears to be utterly benign, a kindly old man, low-key in his demeanor. Indeed, he seems almost bored by what is happening, and so drowsy from the heavy August humidity that he dozes off for a few moments at the bench, but nobody seems to notice, or care. And the defense attorney, Jonathan Marks, carries himself with an air of dignity. He does seem to be concerned that his client be given a fair hearing.

But there appears to be only one difference between Chapman and virtually everybody else who is participating in this hearing: The defendant has far more radical ideas about how far he’s willing to go to achieve celebrity. For one grotesque moment, Chapman, a cowardly loser, an empty shell of a human being, managed to manipulate himself into acting with the courage of his monstrous convictions. He has done exactly what he wanted to do; he has transformed himself into the world’s most famous antihero.

Consequently, the air is thick with vengeful jealousy. People are furious at Chapman not only because he killed John Lennon, but also because he committed a brutal attack on the status quo, an act of class warfare. John Lennon was a very successful professional, a member of the power elite. And the very successful professionals in this courtroom take it personally. Chapman has stolen John Lennon’s fame, and they’re not about to let him enjoy it. But the sad fact is that whatever fleeting fame they might be able to grasp this day will depend strictly upon their relationship to the killer. I psychoanalyzed him. I prosecuted him. I wrote a story about him.

The expert witnesses have prepared well for their moment in the spotlight, for this merging of the personal and historical. The psychiatrists could be mistaken for actors auditioning for a TV miniseries. If there is fault to be found in their performances, it’s that most of them are transparent. They smile too much. They look too happy, too smug, as though they aren’t concerned with any antiquated notions of justice, but are thinking instead about book deals.

The psychiatrists for the prosecution repeat what they’ve been saying since December: Chapman was sane, he knew exactly what he was doing, and he did it for fame. The defense psychiatrists, of course, talk of his schizophrenia, the “Little People,” his pain.

Apparently, nobody on either side is familiar with Yoko Ono’s intriguing statement on reincarnation: “Your brother is the person you murdered in your past life.” So nobody has bothered to ask Chapman, Do you expect to be John Lennon's brother in your next life?

The Lennon fans add a surreal touch to the proceedings. Many of them are long-haired in that “John ’68” style. They wear wire-rimmed glasses and T-shirts with Lennon’s image on it. They’re outnumbered by reporters by at least two to one, and they’re anxious to share their opinions with “the men of the press.”

“Mark David Chapman,” opines one fan, “was just a cowardly fuck who did it for fame.”

“Now he deserves to die,” adds another. “And I’d be happy to pull the switch.”

Allen Sullivan, the prosecutor, describes Chapman as a man who “has never exhibited any true remorse” and who is “only interested in himself, his own well-being, what affects him, what’s important to him at this particular moment.” He then proceeds to hammer home the point that Chapman “did it for fame, personal aggrandizement, to draw attention to himself, to massage his own ego. The defendant was concerned throughout that he become famous.” His proof: Chapman wanted photographer Paul Goresh, who’d previously photographed Lennon signing Chapman’s copy of Double Fantasy, to wait until Lennon returned from his recording session so he could get a photo of the murder.

Sullivan makes it sound as if the desire for fame is a shameful thing, a crime in itself. But his words ring hollow. It’s an ugly show that intentionally overlooks the one hideous fact that hangs like fog in the courtroom. It is the one fact that nobody dares mention: In America in 1981, particularly in a city like New York, fame is a crucial commodity, and anonymity is a toxic condition that can lead to murderous rage.

Holden Caulfield, or John Lennon for that matter, would have puked.

Before Judge Dennis Edwards passes sentence, Chapman is given the opportunity to speak. But there’s little he can do to help himself. Chapman has already pleaded guilty. The evidence against him is overwhelming. There is literally a smoking gun. The verdict may as well have been preordained. He is getting locked up somewhere for the rest of his life. Once, the only real question was if it was going to be in prison or in an institution for the criminally insane. Now there is no question.

Looking like a martyr in a bulletproof vest, he stands up and faces the judge. He has his “Bible” with him–his well-thumbed copy of The Catcher in the Rye. “I’ve chosen this passage as my final spoken words,” he vows–a vow he'll soon break. He opens to Chapter 22, in which Holden, after being thrown out of school for failing four subjects, tells his little sister, Phoebe, what he wants to do with his life.

The murderer begins reading. “Anyway, I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all.” He’s nervous and at first he falters. Then something clicks and he hits his stride, his voice suddenly strong and clear, smooth and flawless. He is well rehearsed, and he does Salinger justice.

“Thousands of little kids and nobody around–nobody big, I mean–except me. And, I’m standing on the edge of some scary cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff–I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all.”

This is his message and confession. Mark David Chapman is the Catcher in the Rye for his generation; he has murdered John Lennon to save the little children.

Then Chapman tells the hushed courtroom, “I feel like a bloodied prizefighter in the 27th round.” These are the exact words he said to a psychiatrist in Hawaii after his suicide attempt. But nobody knows what he’s talking about. They understand neither the significance of 27, the triple 9, nor the significance of Chapter 27, the missing chapter of The Catcher in the Rye, Chapman’s chapter written in Lennon’s blood. They are just the meaningless words of a madman, signifying nothing.

The judge then passes sentence, and Chapman is taken away still wearing manacles. He walks fearlessly out of the courtroom, holding his head high, veritably glowing with pride. He’s done what he came to do.

Afterwards, outside the courtroom, the media, with their pens and floodlights and cameras at the ready, descend upon the expert witnesses for the prosecution, and Sullivan, the prosecutor. They are the winning team. They stand in a tight little knot, preening in the floodlights, everybody smiling broadly, patting each other on the back, congratulating themselves on a job well done. The only thing missing is champagne, which will probably come later, at the private party.

“Was justice served?” the media demands to know.

Of course justice was served. The killer will most likely spend the rest of his life in jail.

Then there is nothing for them to do but go home and watch themselves on the evening news, look at their pictures in the morning newspapers.

Except for Mark David Chapman. He will continue the great fall described in the dark prophesy in Chapter 24 of The Catcher in the Rye. Mr. Antolini, an old teacher of Holden’s–another “pervert,” actually–tells him, “This fall I think you’re riding for–it’s a special kind of fall, a horrible kind. The man falling isn’t permitted to feel or hear himself hit bottom. He just keeps falling and falling.”

Chapman will soon discover what lies at the bottom of the “bottomless” pit: solitary confinement in Attica, possession by demons.

Imagine no possession.

“That kills me.”

That’s what Holden Caulfield would have said, anyway.

From Nowhere Man: The Final Days of John Lennon

Quick American Archives, 2002

© 2000, 2002 Robert Rosen