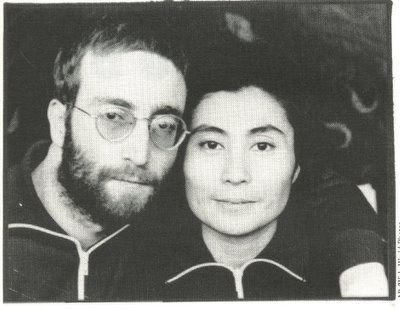

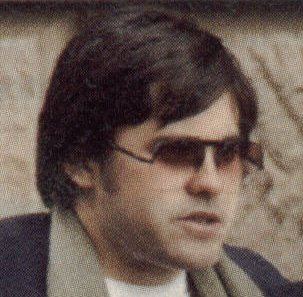

Jared Leto as Mark David Chapman in Chapter 27.

Jared Leto as Mark David Chapman in Chapter 27.As one astute reader of this blog pointed out, Nowhere Man, my John Lennon biography, is not the first book to mention “Chapter 27.” That honor, if I may use such a word, belongs to Jack Jones’s Mark David Chapman bio, Let Me Take You Down, which I used for my own Chapman research and credited accordingly. But one of the flaws in Jones’s book is that he was unaware of the numerological significance of the number 27—that it’s more than the number that follows 26, the final chapter of The Catcher in the Rye—and he didn’t show how Chapter 27 played into the heart of Lennon’s obsession with numerology, the number 9, and all its multiples. Nor did Jones show how, in a very spooky way, the number 27 karmically tied Chapman to Lennon, and gave the events a more chilling resonance. (For a full explanation of all this, please see my first two postings: “The Roots of Chapter 27” and “John Lennon’s Bible and the Occult Significance of 27.”) That’s why Jones mentions Chapter 27 only once, early on in his book, and never elaborates on it.

The Chapman section in Nowhere Man, which I call “The Coda,” picks up where the Jones bio leaves off, bringing Chapter 27 to the forefront of the story. It probes the meaning of what Chapman did more than it plumbs the ooze of Chapman’s mind, from Chapman’s lunatic point of view, as the Jones bio does.

That’s why the only people who seem to fully understand what Chapter 27 means are those who’ve read Nowhere Man or this blog. That’s also why the Mexican newsweekly Proceso has been covering this story in-depth, wasting no time in saying that Chapter 27, the movie, comes from “Chapter 27” in Nowhere Man. In other words, if the producers of Chapter 27 hadn’t read my book, then they’d be calling their film Let Me Take You Down. But they totally get the numerology thing, and they’re placing all their bets on number 27—which is one reason they’re releasing the movie in 2007, probably on September 27.

Some people, presumably enraged Beatles fans, are not happy about this. Perhaps believing that Chapter 27 will inspire other deranged individuals to assassinate a celebrity so they, too, can spend the rest of their lives rotting in jail, these fans are petitioning for a boycott of the film. Apparently, they don’t think that Chapter 27 is getting enough publicity on its own—even with 500 newspapers running stories about Lindsay Lohan’s asthma attacks and Jared Leto’s diet; Yoko Ono herself denouncing the film (except when she’s collaborating on it); and Sean Lennon “dating” Lohan. These fans are also apparently unaware that censorship always backfires.

The case of one Richard M. Nixon should serve as a cautionary tale. The week the Watergate scandal broke in 1972, Nixon, in an attempt to distract the country, ordered the FBI to shut down every theatre showing Deep Throat, confiscate the prints, and arrest the filmmakers and actors on obscenity charges. The result: a mediocre porn flick, shot in a week for $25,000, became the 11th-highest-grossing film of 1973, with earnings of over $600 million, and Linda Lovelace became the world’s first porno “superstar.” (And Nixon still had to resign the presidency, in disgrace, to avoid impeachment.)

I might also remind any aspiring censors that long before Chapman was autographing copies of The Catcher in the Rye in his prison cell, the book was a perennial best-seller, thanks in part to the high school principals all over America who’d been banning it for 29 years.

***

To get a sense of all the “bad karma” swirling around this film, I took a look at the Chapter 27 page on IMDB, the Internet Movie Data Base, which includes a public forum on which I posted a few comments. One of my postings, an attempt to explain the meaning of Chapter 27, prompted another writer, who calls himself Berberis, to talk about his aversion to the word “hate,” which he said “is bandied about on this board—and others—with a willingness I find both alarming and saddening.” Speaking of Chapman, he then asks if the level of hatred towards people we don’t understand is a recent development, or if it’s just easier to express now.

I told him, “Obviously the Internet has made it easy for any maniac who knows how to use a computer to broadcast their hatred worldwide. As for somebody like Chapman: a good way to become a target of virulent hatred is to murder one of the most beloved icons of the 20th century. I, however, think it’s better to make an effort to understand people like Chapman, which is what I did in the final section of Nowhere Man, what Jack Jones did with his Chapman bio—and what I hope the producers of Chapter 27 are doing.

“The original draft of Nowhere Man ended the afternoon of December 8, 1980, before the murder. I wanted to show people what the world looked like through John Lennon’s eyes, and that vision had nothing to do with Chapman. But my publisher insisted that I make an effort to explain what Chapman did—because he didn’t understand it. Since I’d attended the court proceedings and felt I had something new to say—and since the numerology angle gave the story a deeper resonance—I agreed to write the section called ‘The Coda.’

“I was, of course, horrified and repulsed by the murder. But in writing about Chapman, I came to feel a certain sympathy for him because he was (and probably remains) a deeply disturbed human being—the ultimate Nowhere Man.”

Chapter 27 should be allowed to stand or fall on its own. If the film’s a disaster, then the media will crucify it, as they did with Lennon, the clueless Broadway musical, which closed after 40-some-odd performances and lost millions of dollars. But if Chapter 27 is any good—and I hope it is—then it will bring us to a deeper understanding of an event which, on the surface, seems to make no sense at all. And that would be a rare step in the right direction—one that I might even get a little credit for.